Chords & Lyrics to John Cale / You Know More Than I Know

In music, a guitar chord is a set of notes played on a guitar. A chord's notes are often played simultaneously, simply they tin exist played sequentially in an arpeggio. The implementation of guitar chords depends on the guitar tuning. Most guitars used in pop music have half-dozen strings with the "standard" tuning of the Spanish classical guitar, namely E–A–D–G–B–E' (from the lowest pitched string to the highest); in standard tuning, the intervals present amid adjacent strings are perfect fourths except for the major third (G,B). Standard tuning requires four chord-shapes for the major triads.

There are separate chord-forms for chords having their root note on the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth strings. For a six-cord guitar in standard tuning, it may be necessary to driblet or omit i or more than tones from the chord; this is typically the root or fifth. The layout of notes on the fretboard in standard tuning oftentimes forces guitarists to permute the tonal order of notes in a chord.

The playing of conventional chords is simplified past open up tunings, which are especially popular in folk, dejection guitar and not-Spanish classical guitar (such as English and Russian guitar). For example, the typical twelve-bar blues uses simply 3 chords, each of which can be played (in every open up tuning) by fretting six strings with ane finger. Open tunings are used especially for steel guitar and slide guitar. Open tunings allow one-finger chords to be played with greater consonance than do other tunings, which utilize equal temperament, at the price of increasing the racket in other chords.

The playing of (3 to 5 string) guitar chords is simplified by the class of alternative tunings chosen regular tunings, in which the musical intervals are the aforementioned for each pair of sequent strings. Regular tunings include major-thirds tuning, all-fourths, and all-fifths tunings. For each regular tuning, chord patterns may be diagonally shifted down the fretboard, a property that simplifies beginners' learning of chords and that simplifies advanced players' improvisation. On the other hand, in regular tunings 6-string chords (in the keys of C, G, and D) are more difficult to play.

Conventionally, guitarists double notes in a chord to increase its volume, an important technique for players without distension; doubling notes and irresolute the society of notes also changes the timbre of chords. It can make a possible a "chord" which is composed of the all same note on dissimilar strings. Many chords tin be played with the aforementioned notes in more than than one identify on the fretboard.

Musical fundamentals [edit]

The theory of guitar-chords respects harmonic conventions of Western music. Discussions of bones guitar-chords rely on fundamental concepts in music theory: the twelve notes of the octave, musical intervals, chords, and chord progressions.

Intervals [edit]

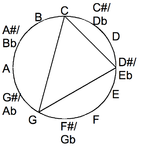

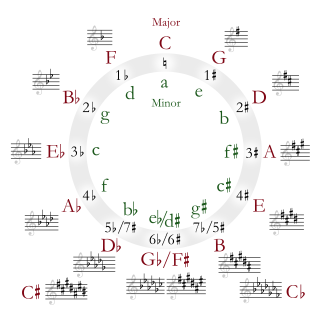

The chromatic circle lists the twelve notes of the octave, which differ by exactly one semitone.

![]()

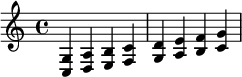

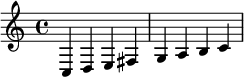

Ane-octave C major scale

Initial eight harmonics on C, namely (C,C,Thousand,C,Due east,G,B ♭ ,C)

The octave consists of twelve notes. Its natural notes institute the C major scale, (C, D, E, F, G, A, B, and C).

The intervals betwixt the notes of a chromatic calibration are listed in a tabular array, in which only the emboldened intervals are discussed in this article's department on fundamental chords; those intervals and other 7th-intervals are discussed in the department on intermediate chords. The unison and octave intervals have perfect consonance. Octave intervals were popularized past the jazz playing of Wes Montgomery. The perfect-fifth interval is highly consonant, which means that the successive playing of the two notes from the perfect 5th sounds harmonious.

A semitone is the distance between 2 side by side notes on the chromatic circumvolve, which displays the twelve notes of an octave.[a]

| Number of semitones | Minor, major, or perfect intervals | Audio | Harmoniousness[ane] [two] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Perfect unison | | Open consonance |

| 1 | Minor second | | Sharp dissonance |

| two | Major second | | Mild dissonance |

| 3 | Minor third | | Soft consonance |

| 4 | Major third | | Soft consonance |

| 5 | Perfect 4th | | Ambiguity |

| vi | Augmented fourth | | Ambiguous |

| 7 | Perfect fifth | | Open consonance |

| viii | Minor sixth | | Soft consonance |

| nine | Major sixth | | Soft consonance |

| 10 | Minor seventh | | Balmy dissonance |

| 11 | Major seventh | | Sharp dissonance |

| 12 | Octave | | Open consonance |

As indicated past their having been emboldened in the table, a scattering of intervals—thirds (minor and major), perfect fifths, and minor sevenths—are used in the following discussion of fundamental guitar-chords.

Equally already stated, the perfect-fifths (P5) interval is the most harmonious, after the unison and octave intervals. An explanation of homo perception of harmony relates the mechanics of a vibrating cord to the musical acoustics of sound waves using the harmonic analysis of Fourier series. When a string is struck with a finger or choice (plectrum), it vibrates according to its harmonic series. When an open-note C-string is struck, its harmonic series begins with the terms (C,C,G,C,E,G,B ♭ ,C). The root note is associated with a sequence of intervals, beginning with the unison interval (C,C), the octave interval (C,C), the perfect 5th (C,G), the perfect quaternary (One thousand,C), and the major third (C,E). In particular, this sequence of intervals contains the thirds of the C-major chord {(C,E),(Eastward,G)}.[3]

With a note of music, one strikes the fundamental, and, in addition to the root note, other notes are generated: these are the harmonic series.... Every bit 1 cardinal annotation contains within it other notes in the octave, two fundamentals produce a remarkable array of harmonics, and the number of possible combinations between all the notes increases phenomenally. With a triad, diplomacy stand a proficient chance of getting severely out of paw.

Perfect fifths [edit]

The perfect-fifth interval is featured in guitar playing and in sequences of chords. The sequence of fifth intervals built on the C-major scale is used in the construction of triads, which is discussed below.[b]

Wheel of fifths [edit]

Concatenating the perfect fifths ((F,C), (C,Grand), (G,D), (D,A), (A,East), (Due east,B),...) yields the sequence of fifths (F,C,G,D,A,E,B,...); this sequence of fifths displays all the notes of the octave.[c] This sequence of fifths shall exist used in the discussions of chord progressions, below.

Ability chord [edit]

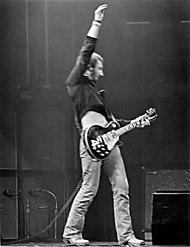

The Who's Peter Townshend ofttimes used a theatrical "windmill" strum to play "power chords"—a root, fifth, and octave.

The perfect-fifth interval is chosen a power chord past guitarists, who play them specially in blues and rock music.[seven] [eight] The Who'south guitarist, Peter Townshend, performed ability chords with a theatrical windmill-strum.[7] [9] Power chords are oftentimes played with the notes repeated in higher octaves.[vii]

Although established, the term "power chord" is inconsistent with the usual definition of a chord in musical theory, which requires three (or more) distinct notes in each chord.[vii]

Chords in music theory [edit]

- A brief overview

C Major (C,E,G) begins with the major tertiary (C,Eastward).

C Minor (C,E ♭ ,1000) begins with minor third (C,E ♭ ).

Major and small triads contain major-third and minor-tertiary intervals in different orders.

The musical theory of chords is reviewed, to provide terminology for a word of guitar chords. Three kinds of chords, which are emphasized in introductions to guitar-playing,[10] [d] are discussed. These bones chords arise in chord-triples that are conventional in Western music, triples that are called 3-chord progressions. After each type of chord is introduced, its role in three-chord progressions is noted.

Intermediate discussions of chords derive both chords and their progressions simultaneously from the harmonization of scales. The basic guitar-chords can exist synthetic past "stacking thirds", that is, by concatenating ii or three tertiary-intervals, where all of the everyman notes come from the scale.[12] [13]

Triads [edit]

Major [edit]

Both major and minor chords are examples of musical triads, which comprise three distinct notes. Triads are often introduced as an ordered triplet:

- the root;

- the third, which is above the root by either a major third (for a major chord) or a minor third (for a small chord);

- the fifth, which is a perfect fifth to a higher place the root; consequently, the 5th is a third above the third—either a minor tertiary above a major tertiary or a major third higher up a minor third.[14] [15] The major triad has a root, a major third, and a fifth. (The major chord'southward major-third interval is replaced by a minor-third interval in the small-scale chord, which shall exist discussed in the next subsection.)

| Chord | Root | Major third | Fifth |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | C | E | G |

| D | D | F ♯ | A |

| East | E | K ♯ | B |

| F | F | A | C |

| G | Yard | B | D |

| A | A | C ♯ | East |

| B[e] | B | D ♯ | F ♯ |

For example, a C-major triad consists of the (root, tertiary, fifth)-notes (C, E, Yard).

The three notes of a major triad have been introduced equally an ordered triplet, namely (root, third, fifth), where the major 3rd is 4 semitones above the root and where the perfect fifth is seven semitones to a higher place the root. This type of triad is in closed position. Triads are quite commonly played in open position: For example, the C-major triad is ofttimes played with the third (Due east) and fifth (G) an octave higher, respectively 16 and nineteen semitones to a higher place the root. Another variation of the major triad changes the order of the notes: For example, the C-major triad is oft played as (C,G,Eastward), where (C,One thousand) is a perfect fifth and East is raised an octave above the perfect 3rd (C,E). Alternative orderings of the notes in a triad are discussed below (in the discussions of chord inversions and drop-2 chords).

In popular music, a subset of triads is emphasized—those with notes from the three major-keys (C, G, D), which also contain the notes of their relative minor keys (Am, Em, Bm).[16]

Progressions [edit]

Stacking the C-major scale with thirds creates a chord progression,

traditionally enumerated with the Roman numerals I, 2, iii, IV, V, 6, vii o . Its major-key sub-progression C–F–Thousand (I–IV–5) is conventional in popular music. In this progression, the small-scale triads two–iii–vi appear in the relative minor key (Am)'southward corresponding chord progression.

The major chords are highlighted by the three-chord theory of chord progressions, which describes the three-chord song that is archetypal in popular music. When played sequentially (in any order), the chords from a three-chord progression audio harmonious ("good together").[f]

The most bones 3-chord progressions of Western harmony accept only major chords. In each central, 3 chords are designated with the Roman numerals (of musical notation): The tonic (I), the subdominant (IV), and the dominant (V). While the chords of each 3-chord progression are numbered (I, Four, and V), they appear in other orders.[f] [xviii]

| Key | Tonic (I) | Subdominant (IV) | Dominant (V) |

| C | C | F | Grand |

| D | D | Thousand | A |

| E | E | A | B |

| One thousand | G | C | D |

| A | A | D | E |

In the 1950s the I–Iv–V chord progression was used in "Hound Dog" (Elvis Presley) and in "Chantilly Lace" (The Big Bopper).[20]

Major-chord progressions are constructed in the harmonization of major scales in triads.[21] For example, stacking the C-major calibration with thirds creates a chord progression, which is traditionally enumerated with the Roman numerals I, ii, iii, IV, V, vi, vii o ; its sub-progression C–F–G (I–Iv–V) is used in popular music,[22] as already discussed. Further chords are constructed by stacking boosted thirds. Stacking the ascendant major-triad with a minor 3rd creates the dominant seventh chord, which shall be discussed after small chords.

Minor [edit]

![]()

An A-minor calibration has the aforementioned pitches as the C major calibration, considering the C major and A minor keys are relative major and small-scale keys.

A pocket-size chord has the root and the fifth of the corresponding major chord, but its offset interval is a pocket-size tertiary rather than a major third:

| Chord | Root | Pocket-size 3rd | Perfect fifth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cm[e] | C | E ♭ | G |

| Dm | D | F | A |

| Em | Eastward | G | B |

| Fm[e] | F | A ♭ | C |

| Gm[e] | G | B ♭ | D |

| Am | A | C | E |

| Bm[east] | B | D | F ♯ |

Minor chords arise in the harmonization of the major scale in thirds, which was already discussed: The minor chords have the degree positions ii, three, and vi.

| Key | Tonic (I) | Subdominant (4) | Dominant (V) |

| Cm | Cm | Fm | G7 |

| Dm | Dm | Gm | A7 |

| Em | Em | Am | B7 |

| Gm | Gm | Cm | D7 |

| Am | Am | Dm | E7 |

Major and small keys that share the same cardinal signature are paired as relative-pocket-sized and relative-major keys.

Minor chords arise every bit the tonic notes of minor keys that share the same key signature with major keys. From the major fundamental'southward I–two–iii–Four–Five–half dozen–vii o progression, the "secondary" (minor) triads ii–iii–vi announced in the relative modest fundamental'due south respective chord progression as i–four–5 (or i–iv–V or i–four–V7): For instance, from C's half-dozen–ii–iii progression Am–Dm–Em, the chord Em is oftentimes played as E or E7 in a modest chord progression.[24] Amongst basic chords, the minor chords (D,East,A) are the tonic chords of the relative minors of the three major keys (F,G,C):

| Key signature | Major key | Minor key |

|---|---|---|

| B ♭ | F major | D minor |

| C major | A minor | |

| F ♯ | G major | E small |

The technique of changing amidst relative keys (pairs of relative majors and relative minors) is a grade of modulation.[25] Minor chords are synthetic by the harmonization of minor scales in triads.[26]

7th chords: major–small-scale chords with ascendant function [edit]

The previously noted chord progression with a dominant seventh ![]() Play(help·info) . The ascendant seventh (V7) chord G7=(G,B,D,F) increases the tension with the tonic (I) chord C.

Play(help·info) . The ascendant seventh (V7) chord G7=(G,B,D,F) increases the tension with the tonic (I) chord C.

Adding a small seventh to a major triad creates a dominant seventh (denoted V7). In music theory, the "dominant seventh" described here is called a major–minor seventh, emphasizing the chord's construction rather than its usual function.[27] Dominant sevenths are often the ascendant chords in 3-chord progressions,[18] in which they increase the tension with the tonic "already inherent in the dominant triad".[28]

| Chord | Root | Major third | Perfect fifth | Pocket-sized 7th |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C7 | C | E | G | B ♭ |

| D7 | D | F ♯ | A | C |

| E7 | E | 1000 ♯ | B | D |

| F7[e] | F | A | C | E ♭ |

| G7 | G | B | D | F |

| A7 | A | C ♯ | E | G |

| B7 | B | D ♯ | F ♯ | A |

The dominant seventh discussed is the about commonly played 7th chord.[29] [thirty]

Paul McCartney used an A-major I–Iv–V7 chord progression in "iii Legs", which is also an example of the twelve-bar blues.

| Central | Tonic (I) | Subdominant (IV) | Dominant (V) |

| C | C | F | G7 |

| D | D | M | A7 |

| Eastward | E | A | B7 |

| G | Yard | C | D7 |

| A | A | D | E7 |

An A-major I–IV–V7 chord progression A–D–E7 was used by Paul McCartney in the vocal "3 Legs" on his album Ram.[32]

These progressions with seventh chords arise in the harmonization of major scales in seventh chords.[33] [g]

Twelve-bar blues [edit]

Be they in major key or pocket-sized key, such I–IV–V chord progressions are extended over twelve bars in popular music—especially in jazz, dejection, and rock music.[36] [37] For example, a twelve-bar dejection progression of chords in the primal of E has three sets of 4 bars:

- E–Due east–E–E7

- A–A–East–East

- B7–A–E–B7;

this progression is simplified by playing the sevenths as major chords.[36] The twelve-bar dejection structure is used by McCartney's "3 Legs",[32] which was noted earlier.

Playing chords: open strings, inversion, and notation doubling [edit]

The implementation of musical chords on guitars depends on the tuning. Since standard tuning is well-nigh commonly used, expositions of guitar chords emphasize the implementation of musical chords on guitars with standard tuning. The implementation of chords using detail tunings is a defining role of the literature on guitar chords, which is omitted in the abstract musical-theory of chords for all instruments.

For example, in the guitar (like other stringed instruments but unlike the piano), open-cord notes are not fretted and and so require less manus-motion. Thus chords that contain open notes are more than easily played and hence more frequently played in pop music, such equally folk music. Many of the most popular tunings—standard tuning, open tunings, and new standard tuning—are rich in the open notes used past popular chords. Open up tunings let major triads to be played by barring one fret with just ane finger, using the finger similar a capo. On guitars without a zeroth fret (afterwards the nut), the intonation of an open note may differ from then annotation when fretted on other strings; consequently, on some guitars, the sound of an open up annotation may exist junior to that of a fretted note.[38]

Unlike the pianoforte, the guitar has the same notes on unlike strings. Consequently, guitar players oft double notes in chord, and so increasing the volume of audio. Doubled notes also changes the chordal timbre: Having unlike "string widths, tensions and tunings, the doubled notes reinforce each other, like the doubled strings of a twelve-string guitar add chorusing and depth".[39] Notes can be doubled at identical pitches or in unlike octaves. For triadic chords, doubling the tertiary interval, which is either a major third or a pocket-size third, clarifies whether the chord is major or small.[40]

Unlike a piano or the voices of a choir, the guitar (in standard tuning) has difficulty playing the chords every bit stacks of thirds, which would crave the left manus to span also many frets,[41] particularly for dominant 7th chords, as explained below. If in a particular tuning chords cannot exist played in closed position, then they often can be played in open up position; similarly, if in a particular tuning chords cannot be played in root position, they can often exist played in inverted positions. A chord is inverted when the bass note is not the root note. Additional chords tin can be generated with drop-two (or drop-3) voicing, which are discussed for standard tuning'south implementation of dominant 7th chords (below).

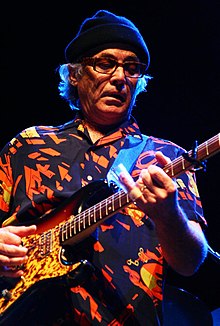

Johnny Marr is known for providing harmony by playing arpeggiated chords.

When providing harmony in accompanying a tune, guitarists may play chords all-at-in one case or every bit arpeggios. Arpeggiation was the traditional method of playing chords for guitarists for instance in the fourth dimension of Mozart. Gimmicky guitarists using arpeggios include Johnny Marr of The Smiths.

Fundamental chords [edit]

Standard tuning [edit]

In the standard guitar tuning, one major third interval is interjected amid four perfect fourth intervals.

In standard tuning, the C-major chord has three shapes because of the irregular major-third between the G- and B-strings.

A 6-cord guitar has five musical-intervals between its consecutive strings. In standard tuning, the intervals are 4 perfect fourths and 1 major tertiary, the comparatively irregular interval for the (G,B) pair. Consequently, standard tuning requires iv chord shapes for the major chords. At that place are separate chord forms for chords having their root note on the tertiary, fourth, fifth, and sixth strings.[42] Of course, a beginner learns guitar by learning notes and chords,[43] and irregularities make learning the guitar difficult[44]—even more difficult than learning the formation of plural nouns in German, according to Gary Marcus.[45] Even so, well-nigh beginners use standard tuning.[46]

Another feature of standard tuning is that the ordering of notes often differs from root position. Notes are often inverted or otherwise permuted, peculiarly with seventh chords in standard tuning,[47] as discussed below.

Power chords: fingerings [edit]

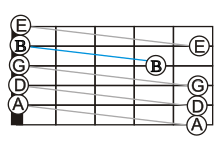

As previously discussed, each power chord has only i interval, a perfect fifth between the root annotation and the fifth.[seven] In standard tuning, the post-obit fingerings are conventional:

-

E5

-

G5

-

G5

Triads [edit]

Triads are usually played with doubled notes,[48] as the post-obit examples illustrate.

Major [edit]

Commonly used major chords are convenient to play in standard tuning, in which cardinal chords are available in open position, that is, the first 3 frets and additional open up strings.

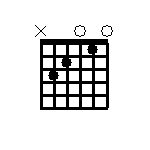

C major chord in open position

For the C major chord (C,E,G), the conventional left-paw fingering doubles the C and E notes in the side by side octave; this fingering uses two open notes, E and Thou:

- E on the first string

- C on the second string

- Thousand on the third cord

- E on the fourth cord

- C on the 5th cord

- Sixth string is non played.[49]

Major Chords (Guide for Guitar Chord Charts)

- A: 002220

- B: x24442

- C: 032010

- D: xx0232

- E: 022100

- F: 133211

- F#: 244322 (movable – recall that no sharps or flats are between BC and EF)

- Normal One thousand: 320003

- Nashville manner Grand: 3×0033

For the other normally used chords, the conventional fingerings also double notes and feature open-string notes:

-

A Major Chord

-

D Major Chord

-

E Major Chord

-

K Major Chord

Besides doubling the fifth notation, the conventional E-major chord features a tripled bass note.[48]

A barre chord ("E Major shape"), with the alphabetize finger used to bar the strings

The B major and F major chords are commonly played as barre chords, with the start finger depressing five–six strings.

-

B Major Chord

-

F Major Chord

B major chord has the same shape as the A major chord merely information technology is located ii frets further upwardly the fretboard. The F major chord is the aforementioned shape as Due east major merely information technology is located one fret further up the fretboard.

Small-scale [edit]

Minor chords (unremarkably notated equally C-, Cm, Cmi or Cmin) are the aforementioned every bit major chords except that they take a minor tertiary instead of a major 3rd. This is a difference of i semitone.

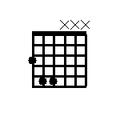

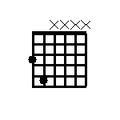

To create F modest from the F major chord (in E major shape), the 2nd finger should be lifted so that the third string plays onto the barre. Compare the F major to F minor:

-

F Major Chord

-

F Modest Chord

The other shapes tin be modified as well:

| Chord proper name | Fret numbers |

|---|---|

| E small | [0 2 ii 0 0 0] |

| A pocket-size | [X 0 ii 2 1 0] |

| D minor | [X X 0 two 3 i] |

Suspended [edit]

Movable Suspended Chords Guide (for chord charts)

(in standard tuning)

Sus2

- A Sus2 x02200

- B Sus2 x24422

- C Sus2 x35533

- D Sus2 x00230

Sus4

- E SUS4 022200

- F SUS4 133311

- G SUS4 355533

These chords are used extensively by My Bloody Valentine, on the album Loveless. They are also used on the Who song "Pinball Wizard" and many, many more songs.

Dominant sevenths: drop two [edit]

In standard tuning, the C7 chord has notes on frets 3–8. Roofing six frets is hard, and so C7 is rarely played. Instead, an "culling voicing" is substituted.

As previously stated, a dominant seventh is a four-note chord combining a major chord and a pocket-size 7th. For example, the C7 dominant seventh chord adds B ♭ to the C-major chord (C,E,Yard). The naive chord (C,E,G,B ♭ ) spans six frets from fret iii to fret 8;[l] such seventh chords "contain some pretty serious stretches in the left manus".[47] An illustration shows a naive C7 chord, which would be extremely difficult to play,[50] besides the open up-position C7 chord that is conventional in standard tuning.[50] [h] The standard-tuning implementation of a C7 chord is a second-inversion C7 driblet two chord, in which the second highest annotation in a second inversion of the C7 chord is lowered by an octave.[fifty] [52] [53] Drop-ii chords are used for sevenths chords besides the major–minor seventh with ascendant function,[54] which are discussed in the department on intermediate chords, below. Drop-two chords are used particularly in jazz guitar.[55] Drib-two 2nd-inversions are examples of openly voiced chords, which are typical of standard tuning and other popular guitar tunings.[i]

"Alternatively voiced" seventh chords are unremarkably played with standard tuning. A list of fret number configurations for some common chords follows:

- E7:[020100]

- G7:[320001]

- A7:[X02020]

- B7:[X21202] (This B7 requires no barre, unlike the B major.)

- D7:[XX0212]

Other chord inversions [edit]

Already in bones guitar playing, inversion is important for sevenths chords in standard tuning. Information technology is too important for playing major chords.

In standard tuning, chord inversion depends on the bass note's cord, and so there are iii unlike forms for the inversion of each major chord, depending on the position of the irregular major thirds interval between the G and B strings.

For example, if the note Eastward (the open up 6th string) is played over the A minor chord, and so the chord would be [0 0 ii 2 1 0]. This has the notation Eastward as its everyman tone instead of A. Information technology is ofttimes written as Am/E, where the letter following the slash indicates the new bass note. Yet, in popular music it is usual to play inverted chords on the guitar when they are not role of the harmony, since the bass guitar tin can play the root pitch.

Alternate tunings [edit]

Chords have consequent shapes everywhere on the fretboard for each regular tuning, for example, major-thirds (M3) tuning.

Chords tin can be shifted diagonally in regular tunings.

There are many alternate tunings. These modify the way chords are played, making some chords easier to play and others harder.

- Open up tunings each allow a chord to be played by strumming the strings when "open", or while fretting no strings.[57] [58] Open tunings are mutual in blues and folk music,[59] and they are used in the playing of slide guitar.[lx] [61]

- Driblet tunings are common in hard rock and heavy metal music. In drop-D tuning, the standard tuning's Eastward-string is tuned down to a D notation. With driblet-D tuning, the bottom three strings are tuned to a root–5th–octave (D–A–D) tuning, which simplifies the playing of power chords.[62] [63]

- Regular tunings permit chord note-forms to exist shifted all around the fretboard, on all six strings (unlike standard or other not-regular tunings). Knowing a few note-patterns—for example of the C major, C pocket-size, and C7 chords—enables a guitarist to play all such chords.Sethares (2009, p. ii) "Acquire a scattering of chord forms in a regular tuning, and you'll know hundreds of chords!"</ref>

Open tunings [edit]

An open tuning allows a chord to be played by strumming the strings when "open", or while fretting no strings. The base chord consists of at least 3 notes and may include all the strings or a subset. The tuning is named for the base of operations chord when played open, typically a major triad, and each major triad tin can be played by disallowment exactly one fret.[60] Open tunings are common in blues and folk music,[59] and they are used in the playing of slide and lap-slide ("Hawaiian") guitars.[60] [61] Ry Cooder uses open tunings when he plays slide guitar.[59]

Open tunings improve the intonation of major chords by reducing the mistake of third intervals in equal temperaments. For example, in the open-G overtones tuning M–One thousand–D–G–B–D, the (One thousand,B) interval is a major tertiary, and of form each successive pair of notes on the Thousand- and B-strings is also a major third; similarly, the open-string minor-third (B,D) induces small thirds amidst all the frets of the B-D strings. The thirds of equal temperament have audible deviations from the thirds of only intonation: Equal temperaments is used in modernistic music because it facilitates music in all keys, while (on a piano and other instruments) but intonation provided better-sounding major-third intervals for only a subset of keys.[64] "Sonny Landreth, Keith Richards and other open up-G masters often lower the second string slightly then the major third is in tune with the overtone series. This aligning dials out the noise, and makes those big 1-finger major-chords come alive."[65]

Repetitive open up-tunings are used for 2 not-Spanish classical-guitars. For the English guitar the open chord is C major (C–E–G–C–Eastward–1000);[66] for the Russian guitar which has 7 strings, G major (G–B–D–Grand–B–D–G).[67] [68] [69] Mixing a perfect fourth and a small-scale third along with a major third, these tunings are on-average major-thirds regular-tunings. While on-average major-thirds tunings are conventional open tunings, properly major-thirds tunings are unconventional open-tunings, because they accept augmented triads as their open chords.[lxx]

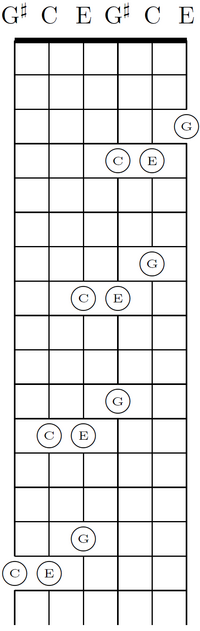

Regular tunings [edit]

Guitar chords are dramatically simplified by the class of alternative tunings called regular tunings. In each regular tuning, the musical intervals are the same for each pair of consecutive strings. Regular tunings include major-thirds (M3), all-fourths, augmented-fourths, and all-fifths tunings. For each regular tuning, chord patterns may be diagonally shifted down the fretboard, a property that simplifies beginners' learning of chords and that simplifies avant-garde players' improvisation.[71] [72] [73] The diagonal shifting of a C major chord in M3 tuning appears in a diagram.

Major-thirds tuning repeats its notes after iii strings.

Farther simplifications occur for the regular tunings that are repetitive, that is, which repeat their strings. For case, the E–M ♯ –c–e–chiliad ♯ –c' M3 tuning repeats its octave after every two strings. Such repetition further simplifies the learning of chords and improvisation;[72] This repetition results in two copies of the three open-strings' notes, each in a dissimilar octave. Similarly, the B–F–B–F–B–F augmented-fourths tuning repeats itself after i string.[74]

In major-thirds tuning, chords are inverted by raising notes by three strings on the same frets. The inversions of a C major chord are shown.[75]

A chord is inverted when the bass note is non the root note. Chord inversion is particularly simple in M3 tuning. Chords are inverted simply past raising one or two notes by iii strings; each raised note is played with the aforementioned finger as the original note. Inverted major and minor chords can be played on two frets in M3 tuning.[75] [76] In standard tuning, the shape of inversions depends on the involvement of the irregular major 3rd, and tin involve four frets.[77]

It is a claiming to adapt conventional guitar chords to new standard tuning, which is based on all-fifths tuning.[j]

Intermediate chords [edit]

Later on major and minor triads are learned, intermediate guitarists play seventh chords.

Tertian harmonization [edit]

- Stacking of 3rd intervals

The key guitar-chords—major and minor triads and dominant sevenths—are tertian chords, which concatenate third intervals, with each such 3rd being either major (M3) or minor (m3).

More triads: macerated and augmented [edit]

As discussed above, major and small triads are synthetic by stacking thirds:

- The major triad concatenates (M3,m3), supplementing M3 with a perfect-5th (P5) interval, and

- the modest triad concatenates (m3, M3), supplementing m3 with a P5 interval.

Like tertian harmonization yields the remaining two triads:

- the macerated triad concatenates (m3,m3), supplementing m3 with a diminished-fifth interval, and

- the augmented triad concatenates (M3,M3), supplementing M3 with an augmented-fifth interval.

More sevenths: major, minor, and (half-)diminished [edit]

Stacking thirds as well constructs the almost used seventh-chords. The most important seventh-chords concatenate a major triad with a 3rd interval, supplementing it with a seventh interval:

- The (dominant) major-pocket-sized seventh concatenates a major triad with some other small-scale third, supplementing information technology with a modest-seventh interval.

- The major 7th concatenates a major triad with a major tertiary, supplementing it with a major-seventh interval.

- The pocket-sized seventh concatenates a small-scale triad with a minor 3rd, supplementing it with a minor-seventh interval.

- The half-macerated seventh concatenates a diminished triad with a major third, supplementing it with a diminished-seventh interval.

- The (fully) diminished seventh concatenates a diminished triad with a modest third, supplementing it with a diminished-seventh interval.[79]

Four of these 5 7th-chords—all but the macerated seventh—are synthetic via the tertian harmonization of a major scale.[80] As already stated,

- The major-minor seventh has the ascendant V7 function.

- The major 7th plays the tonic (I7) and subdominant (IVseven) roles;

- The minor 7th plays the 2seven, iii7, and 67 roles.

- The one-half-macerated seventh plays the vii ø 7 function.

While absent from the tertian harmonization of the major scale,

- The diminished seventh plays the vii o 7 role in the tertian harmonization of the harmonic pocket-size scale.[80]

Likewise these v types there are many more 7th-chords, which are less used in the tonal harmony of the common-exercise menstruation.[79]

When playing 7th chords, guitarists oftentimes play only subset of notes from the chord. The fifth is often omitted. When a guitar is accompanied past a bass, the guitarist may omit the bass note from a chord. Every bit discussed before, the third of a triad is doubled to emphasize its major or minor quality; similarly, the tertiary of a seventh is doubled to emphasize its major or minor quality. The nigh frequent seventh is the dominant seventh; the minor, half-diminished, and major sevenths are as well popular.[81]

Chord progression: circle of fifths [edit]

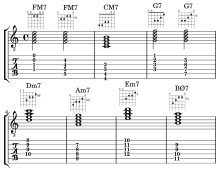

Sevenths chords arising in the tertian harmonization of the C-major scale, arranged past the circle of perfect fifths (perfect fourths). Fretboard diagrams for major-thirds tuning are shown. ![]() FifthsC.mid(assistance·info)

FifthsC.mid(assistance·info)

The previously discussed I–IV–Five chord progressions of major triads is a subsequence of the circle progression, which ascends past perfect fourths and descends by perfect fifths: Perfect fifths and perfect fourths are changed intervals, because 1 reaches the aforementioned pitch class by either ascending by a perfect 4th (five semitones) or descending by a perfect 5th (seven semitones). For example, the jazz standard "Autumn Leaves" contains the four7–Seven7–VIM7–ii ø 7–i circle-of-fifths chord progression;[82] its sevenths occur in the tertian harmonization in sevenths of the modest scale.[83] Other subsequences of the fifths-circle chord progression are used in music. In particular, the ii–V–I progression is the near important chord progression in jazz music.

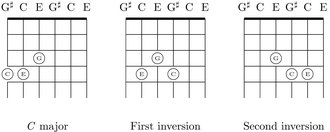

Chord chart guide for major inversions [edit]

Major inversions for guitar in standard tuning. The depression E is on the left. The A demonstrates 3 of the different movable shapes.

- A: [XXX655] | A: [XXX9(10)nine] | A: [XXX220]

- B: [XXX442]

- C: [XXX553]

- D: [XXX775]

- East: [XXX997]

- F: [XXX211]

- G: [XXX433] [84]

Specific tunings [edit]

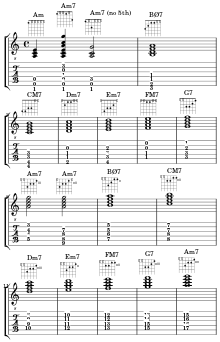

Standard tuning: small and major sevenths [edit]

Besides the ascendant seventh chords discussed above, other seventh chords—especially pocket-size seventh chords and major seventh chords—are used in guitar music.

Small-scale seventh chords have the post-obit fingerings in standard tuning:

- Dm7: [XX0211]

- Em7: [020000]

- Am7: [X02010]

- Bm7: [X20202]

- F ♯ m7: [202220] or ([XX2222] Too an A/F ♯ Chord)

Major seventh chords have the post-obit fingerings in standard tuning:

- Cmaj7: [X32000]

- Dmaj7: [XX0222]

- Emaj7: [021100]

- Fmaj7: [103210]

- Gmaj7: [320002]

- Amaj7: [X02120]

Major-thirds tuning [edit]

In major-thirds (M3) tuning, the chromatic scale is arranged on 3 consecutive strings in iv consecutive frets.[85] [86] This 4-fret arrangement facilitates the left-hand technique for classical (Spanish) guitar:[86] For each hand position of four frets, the hand is stationary and the fingers move, each finger being responsible for exactly ane fret.[87] Consequently, three hand positions (roofing frets 1–4, 5–eight, and 9–12) partition the fingerboard of classical guitar,[88] which has exactly 12 frets.[k]

Only 2 or 3 frets are needed for the guitar chords—major, small, and dominant sevenths—which are emphasized in introductions to guitar-playing and to the fundamentals of music.[91] [92] Each major and minor chord can be played on exactly 2 successive frets on exactly three successive strings, and therefore each needs only two fingers. Other chords—seconds, fourths, sevenths, and ninths—are played on only three successive frets.[93]

Advanced chords and harmony [edit]

Sequences of thirds and seconds [edit]

The circle of fifths was discussed in the section on intermediate guitar chords. Other progressions are also based on sequences of third intervals;[94] progressions are occasionally based on sequences of second intervals.[95]

Extended chords [edit]

As their categorical name suggests, extended chords indeed extend seventh chords by stacking i or more additional third-intervals, successively constructing ninth, eleventh, and finally thirteenth chords; thirteenth chords contain all seven notes of the diatonic scale. In closed position, extended chords contain dissonant intervals or may sound supersaturated, particularly thirteenth chords with their vii notes. Consequently, extended chords are oft played with the omission of one or more tones, specially the fifth and oft the third,[96] [97] as already noted for seventh chords; similarly, eleventh chords often omit the ninth, and thirteenth chords the 9th or eleventh. Often, the tertiary is raised an octave, mimicking its position in the root's sequence of harmonics.[96]

Ascendant ninth chords were used past Beethoven, and eleventh chords appeared in Impressionist music. Thirteenth chords appeared in the twentieth century.[98] Extended chords announced in many musical genres, including jazz, funk, rhythm and blues, and progressive rock.[97]

Chord guide for major and minor 9 chords [edit]

(Standard tuning, read from left to right, depression Due east to high e)

Major 9

- AM9: [XX7454]

- BbM9: [XX8565]

- BM9: [XX9676]

- CM9: [XX(ten)787]

- C#M9: [XX(11)898]

- DM9: [XX0220]

- EM9: [099800]

- FM9: [XX3010]

- GM9: [XX5232]

Minor 9

- Am9: [575557]

- Bm9: [797779]

- Cm9: [X3133X]

- Dm9: [X5355X]

- Em9: [X7577X]

- Fm9: [X8688X]

- Gm9: [353335] [99]

Alternative harmonies [edit]

Scales and modes [edit]

Conventional music uses diatonic harmony, the major and small keys and major and minor scales, equally sketched above. Jazz guitarists must be fluent with jazz chords and also with many scales and modes; "of all the forms of music, jazz ... demands the highest level of musicianship—in terms of both theory and technique".[100]

Whole tone scales were used by King Crimson for the title track on its Red album of 1974;[101] [102] whole tone scales were also used by King Crimson guitarist Robert Fripp on "Fractured".[101]

Beyond tertian harmony [edit]

Disliking the audio of thirds (in equal-temperament tuning), Robert Fripp builds chords with perfect intervals in his new standard tuning.

In popular music, chords are oftentimes extended also with added tones, particularly added sixths.[103]

Quartal and quintal harmony [edit]

Chords are also systematically constructed by stacking not only thirds but also fourths and fifths, supplementing tertian major–pocket-size harmony with quartal and quintal harmonies. Quartal and quintal harmonies are used by guitarists who play jazz, folk, and rock music.

Quartal harmony has been used in jazz by guitarists such every bit Jim Hall (especially on Sonny Rollins's The Bridge), George Benson ("Skydive"), Kenny Burrell ("And then What"), and Wes Montgomery ("Little Sunflower").[104]

Harmonies based on fourths and fifths as well appear in folk guitar. On her 1968 debut album Vocal to a Seagull, Joni Mitchell used both quartal and quintal harmony in "Dawntreader", and she used quintal harmony in "Seagull".[105]

Quartal and quintal harmonies also announced in alternate tunings. It is easier to finger the chords that are based on perfect fifths in new standard tuning than in standard tuning. New standard tuning was invented by Robert Fripp, a guitarist for King Crimson. Preferring to base chords on perfect intervals—specially octaves, fifths, and fourths—Fripp often avoids small-scale thirds and especially major thirds,[106] which are sharp in equal temperament tuning (in comparison to thirds in just intonation).

Culling harmonies tin can too be generated past stacking second intervals (major or small).[107]

Meet also [edit]

- Chord diagram (guitar)

- Mel Bay's Palatial Encyclopedia of Guitar Chords

- Phonation leading

References [edit]

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ An octave is the interval between 1 musical pitch and another with double (or half) its frequency.

- ^ This sequence of fifths features the diminished fifth (b,f), which replaces the perfect fifth (b,f ♯ ) containing the chromatic note f ♯ , which is non a member of the C-major key. The annotation f (of the C-major scale) is replaced by the note f ♯ in the Lydian chromatic scale.[five]

- ^ Perfect fifths have been emphasized since the chants and hymns of medieval Christendom, co-ordinate to the medieval musical-theory called the organum.[6]

- ^ Denyer (1992) and Schmid & Kolb (2002) each list the same 15 chords for beginners: Am, A, A7; B7; C, C7; Dm, D, D7; Em, E, E7; F; G, G7.[xi]

- ^ a b c d e f This chord does not announced among the 15 basic-chords listed independently by Denyer and by Schmid and Kolb: Am, A, A7; B7; C, C7; Dm, D, D7; Em, E, E7; F; G, G7.[eleven]

- ^ a b c Roman numeral analysis.[17]

- ^ The harmony of major chords has dominated music since the Bizarre era (17th and 18th centuries).[34] The Bizarre menstruum besides introduced the dominant seventh.[35]

- ^ The alternative voicing of the C7 chord follows the first seventh-chord diagram of (Denyer 1992).[51]

- ^ Closed voicings, which are typical of pocket-size-thirds tuning, are typical as well of a keyboard or piano.[56]

- ^ Musicologist Eric Tamm wrote that despite "considerable effort and search I just could not find a good prepare of chords whose sound I liked" for rhythm guitar.[78]

- ^ Classical guitars have 12 frets, while steel-string acoustics have xiv or more.[89] Electrical guitars have more than frets, for example 20.[90]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Persichetti 1961, p. 14.

- ^ Denyer 1992, Playing the guitar: The harmonic guitarist; Intervals: Interval nautical chart, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Persichetti 1961, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Denyer 1992, p. 114.

- ^ Russell 2001, "The primal harmonic construction of the Lydian calibration", Case one:seven, "The C Lydian scale", p. five.

- ^ Duarter 2008, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e Denyer (1992, "The avant-garde guitarist; Power chords and fret tapping: Power chords", p. 156)

- ^ Kolb 2005, "Chapter 7: Chord structure; Suspended chords, power chords, and 'add' chords", p. 42.

- ^ Denyer 1992, "The Guitar Innovators: Pete Townshend", pp. 22–23.

- ^ Mead 2002, pp. 28 and 81, compare p. 40.

- ^ a b Denyer (1992, The beginner, Open chords, The beginner's chord lexicon, pp. 74–75) and Schmid & Kolb (2002, Chord chart, p. 47).

- ^ Denyer 1992, pp. 123–125.

- ^ Kolb 2005, Chapter 6: Harmonizing the major scale, pp. 35–38; Chapter 7: Chord construction, pp. forty–48; and Chapter 8: Harmonizing the pocket-size scale, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Duckworth 2007, Affiliate 11 "Triads" and Chapter 12 "Triads in a musical context".

- ^ Kolb (2005, Chapter five: Triads, Major and minor triads, pp. 30-31)

- ^ Griewank (2010, p. 5)

- ^ Denyer 1992, "The beginner: The three-chord theory, Chords built on the major scale in five common keys", p. 76.

- ^ a b c d Denyer (1992, "The beginner: The three-chord theory, Chord progressions based on the three-chord theory", p. 77)

- ^ Kolb 2005, Chapter 6: Harmonizing the major scale, Diatonic triads, Figure3, Harmonized major scales (triads), p. 38.

- ^ Everett 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Kolb 2005, Affiliate half-dozen: Harmonizing the major scale: Diatonic triads, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Duckworth 2007, p. 239.

- ^ Kolb 2005, Chapter 8: Harmonizing the major scale, Figure iv, Harmonized pocket-sized scales (triads), p. 50.

- ^ Denyer 1992, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Duckworth 2007, p. 156.

- ^ Kolb 2005, Chapter eight: Harmonizing the minor scale, Minor scale triads, pp. 49–fifty.

- ^ Kostka, Payne & Almén 2013, Chapter 3: Introduction to triads and seventh chords, Seventh chords, pp. 40–41, and Chapter 13: The V7 chord, p. 198.

- ^ Duckworth 2007, p. 245.

- ^ Kostka, Payne & Almén 2013, Chapter three: Introduction to triads and seventh chords, Seventh chords, p. 40–41, Chapter 13: The 57 chord, p. 198, and Affiliate 14, The II7 and VII7 chords, p. 217.

- ^ Kolb 2005, Chapter 6: Harmonizing the major scale, Diatonic seventh chords, pp. 37–38; Chapter 7: Chord construction, Seventh chords, Diminished seventh, dominant seventh SUS4, and pocket-sized(maj7) chords, pp. 44–45; Affiliate 8: Harmonizing the minor scale: Minor scale seventh chords, p. 51.

- ^ Kolb 2005, Chapter half-dozen: Figure 5, Harmonized major scales (seventh chords), p. 38.

- ^ a b Benitez (2010, p. 29)

- ^ Kolb 2005, Chapter 6: Harmonizing the major scale, Diatonic seventh chords, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 100.

- ^ Benward & Saker 2003, p. 201.

- ^ a b Denyer (1992, "The beginner: The iii-chord theory: Blues chord progressions, p. 77)

- ^ Kolb 2005, Affiliate 10: Blues harmony and pentatonic scales, The 12-bar blues progression", pp. 61–62.

- ^ LeVan, John (December 2007). "Get Nuts!". Acoustic Guitar. String Letter Publishing. [ dead link ]

- ^ Sethares (2001, pp. 54)

- ^ Denyer (1992, "The harmonic guitarist: Interval inversions, Triad doubling", p. 123)

- ^ Clendinning & Marvin 2005, p. 181.

- ^ Denyer 1992, p. 119.

- ^ Marcus 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Marcus 2012, pp. 40–43.

- ^ Marcus 2012, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Marcus 2012, p. 181.

- ^ a b Kolb (2005, Chapter 6: Harmonizing the major scale: Diatonic seventh chords, p. 37)

- ^ a b Roche (2004, p. 104)

- ^ Denyer 1992, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Smith (2010, pp. 92–93)

- ^ Denyer 1992, "The harmonic guitarist: 7th chords: The dominant seventh chords", p. 127.

- ^ Chapman 2000, p. half-dozen.

- ^ Fisher 2002, 'Drop voicing' and '7th chords in driblet 2 and drop 3 voicings', pp. 30–33.

- ^ Willmott 1994, Chapter 1: Drib 2 type voicings, pp. 8–13.

- ^ Vincent 2011, pp. 2–7.

- ^ Sethares 2001, "The small-scale tertiary tuning", p. 54.

- ^ Roche (2004, "Open tunings", pp. 156–159)

- ^ Roche (2004, "Cross-note tunings", p. 166)

- ^ a b c Denyer (1992, p. 158)

- ^ a b c Sethares (2009, p. 16)

- ^ a b Denyer (1992, p. 160)

- ^ Roche (2004, pp. 153–156)

- ^ Denyer (1992, pp. 158–159)

- ^ Gold, Jude (1 December 2005). "Only desserts: Steve Kimock shares the sweet sounds of justly tuned thirds and sevenths". Master class. Guitar Player. [ dead link ]

- ^ Gold, Jude (June 2007). "Fender VG Stratocaster". Gear: Bench Test (Production/service evaluation). Guitar Player. Archived from the original on xvi January 2013.

- ^ Annala & Mätlik 2007, p. 30.

- ^ Ophee, Matanya (ed.). 19th Century etudes for the Russian 7-string guitar in Thousand Op. The Russian Collection. Vol. ix. Editions Orphee. PR.494028230. Archived from the original on iv July 2013.

- ^ Ophee, Matanya (ed.). Selected Concert Works for the Russian 7-String Guitar in G open up tuning. The Russian Collection. Vol. 10. Editions Orphee. PR.494028240. Archived from the original on iv July 2013.

- ^ Timofeyev 1999, p.[ page needed ].

- ^ Sethares (2001, "The major tertiary tuning", pp. 56–57)

- ^ Griewank (2010, p. 3)

- ^ a b Kirkeby, Ole. "Major thirds tuning". M3 Guitar. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved ten June 2012. Cited past Sethares (2012) and Griewank (2010, p. 1)

- ^ Sethares (2001, p. 52)

- ^ Sethares 2001, p. 58.

- ^ a b Kirkeby, Ole. "Fretmaps, Major Chords". M3 Guitar. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012.

- ^ Griewank (2010, p. 10)

- ^ Denyer (1992, p. "Triads: Triad inversions", p. 121)

- ^ Tamm 2003.

- ^ a b Kostka, Payne & Almén (2013, pp. 40–41)

- ^ a b Kostka, Payne & Almén (2013, pp. 61–62 and 65)

- ^ a b Kostka, Payne & Almén (2013, p. 217)

- ^ Kostka, Payne & Almén (2013, pp. 238 and 46)

- ^ Kolb 2005, p. 51.

- ^ "Major Chord Inversion Guitar Lesson". thoughtco.com. Archived from the original on xiv October 2017.

- ^ Peterson (2002, pp. 36–37)

- ^ a b Griewank (2010, p. 9)

- ^ Denyer (1992, p. 72)

- ^ Peterson (2002, p. 37)

- ^ Denyer 1992, p. 45.

- ^ Denyer 1992, p. 77.

- ^ Mead 2002, pp. 28 and 81.

- ^ Duckworth 2007, p. 339.

- ^ Griewank (2010, p. two)

- ^ Kostka, Payne & Almén 2013, pp. 430–438 and 442–446.

- ^ Kostka, Payne & Almén 2013, p. 475.

- ^ a b Kostka, Payne & Almén (2013, Affiliate 26: Materials and techniques, Chord structures, p. 465)

- ^ a b Kolb (2005, p. 45)

- ^ Kostka, Payne & Almén 2013, Chapter 26: Materials and techniques, Chord structures, p. 464.

- ^ Cranwell, Jim. "Superstrings Guitar Chord Name Finder". Gootar.com. Archived from the original on nineteen October 2017.

- ^ Denyer (1992, p. 101)

- ^ a b Macon (1997, p. 55)

- ^ Tamm 1995, p. 85.

- ^ Clendinning & Marvin 2005, p. 511.

- ^ Floyd 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Whitesell 2008, pp. 131 and 202–203.

- ^ Mulhern, Tom (January 1986). "On the bailiwick of arts and crafts and art: An interview with Robert Fripp". Guitar Thespian. 20: 88–103. Archived from the original on sixteen Feb 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ^ Kostka, Payne & Almén 2013, pp. 470–471.

Bibliography [edit]

- Annala, Hannu; Mätlik, Heiki (2007). "Composers for other plucked instruments: Rudolf Straube (1717–1785)". Handbook of Guitar and Lute Composers. Translated past Katarina Backman. Mel Bay. ISBN978-0-786-65844-2.

- Benitez, Vincent Perez (2010). "The remaking of a Beatle: Paul McCartney every bit solo artist, 1970–71". The Words and Music of Paul McCartney: The Solo Years. Praeger. pp. xix–35. ISBN978-0-313-34969-0.

- Benward; Saker (2003). Music: In theory and do. Vol. I (7th ed.). ISBN978-0-07-294262-0.

- Chapman, Charles (2000). Drop-2 concept for guitar. Mel Bay Publications. ISBN0786644834.

- Clendinning, Jane Piper; Marvin, Elizabeth Westward (2005). The musician's guide to theory and assay (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton and Visitor. ISBN0-393-97652-i.

- Denyer, Ralph (1992). "Playing the guitar, pp. 65–160, and The chord lexicon, pp. 225–249". The guitar handbook. Special contributors Isaac Guillory and Alastair M. Crawford. London and Sydney: Pan Books. ISBN0-330-32750-X.

- Duarter, John (2008). Tune and harmony for guitarists. ISBN978-0-7866-7688-0.

- Duckworth, William (2007). A artistic approach to music fundamentals: Includes keyboard and guitar insert (ninth ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Schirmer. pp. 1–384. ISBN978-0-495-09093-9.

- Everett, Walter (2008). The foundations of rock: From "Blue Suede Shoes" to "Suite: Judy Blue Optics". Oxford University Press. pp. i–442. ISBN978-0-19-531024-5.

- Fisher, Jody (2002). "Chapter 5: Expanding your vii chord vocabulary". Jazz guitar harmony: Take the mystery out of jazz harmony. Alfred Music Publishing. pp. 26–33. ISBN073902468X. UPC 038081196275.

- Floyd, Tom (2004). Quartal harmony & voicings for guitar. Mel Bay Publications. ISBN0-7866-6811-3.

- Griewank, Andreas (iv Jan 2010), Tuning guitars and reading music in major thirds, Matheon preprints, vol. 695, Berlin, Federal republic of germany: DFG inquiry middle "MATHEON, Mathematics for key technologies" Berlin, MSC-Classification 97M80 Arts. Music. Language. Architecture (Postscript file and PDF file)

- Kolb, Tom (2005). Music theory. Hal Leonard Guitar Method. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. one–104. ISBN0-634-06651-X.

- Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy; Almén, Byron (2013). Tonal Harmony, with an Introduction to Twentieth-century Music (seventh ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN978-0-07-131828-0.

- Macon, Edward L. (1997). Rocking the classics: English progressive rock and the counterculture . Oxford and New York: Oxford University. ISBN0-19-509887-0.

- Marcus, Gary (2012). Guitar zero: The science of learning to be musical. Oneworld. ISBN9781851689323.

- Mead, David (2002). Chords and scales for guitarists. London: Bobcat Books Limited: SMT. ISBN978-1860744327.

- Persichetti, Vincent (1961). Twentieth-century harmony: Creative aspects and practice . New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN0-393-09539-8. OCLC 398434.

- Peterson, Jonathon (2002). "Tuning in thirds: A new arroyo to playing leads to a new kind of guitar". American Lutherie: The Quarterly Journal of the Guild of American Luthiers. Tacoma, WA: The Guild of American Luthiers. 72 (Winter): 36–43. ISSN 1041-7176. Archived from the original on 21 October 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- Roche, Eric (2004). "3 I-man band, 4 Exploring the fingerboard, 5 Thinking exterior the box". The audio-visual guitar Bible. London: Bobcat Books Limited, SMT. pp. 74–109, 110–150, and 151–178. ISBN186074432X.

- Russell, George (2001) [1953]. "Affiliate 1 The Lydian scale: The seminal source of the master of tonal gravity". George Russell's Lydian chromatic concept of tonal arrangement. Vol. Ane: The art and science of tonal gravity (4th ed.). Brookline, Massachusetts: Concept Publishing Company. pp. i–9. ISBN0-9703739-0-2. (Second printing, corrected, 2008)

- Schmid, Will; Kolb, Tom (2002). "Chord nautical chart". Guitar method: Book ane. Hal Leonard Guitar Method (2d ed.). Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 47. ISBN0-7935-3392-ix.

- Sethares, Pecker (2001). "Regular tunings". Alternate tuning guide (PDF). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin; Section of Electrical Engineering. pp. 52–67. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Sethares, Bill (10 January 2009) [2001]. Alternating tuning guide (PDF). Madison, Wisconsin: Academy of Wisconsin; Department of Electrical Technology. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Sethares, William A. (xviii May 2012). "Alternate tuning guide". Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin; Department of Electrical Technology. Retrieved 8 Dec 2012.

- Smith, Johnny (2010). "XVII: Upper structure inversions of the dominant seventh chords". Mel Bay's complete Johnny Smith approach to guitar. Complete series. Mel Bay Publications. pp. 92–97. ISBN978-i-6097-4959-0.

- Tamm, Eric (1995) [1989]. "Chapter 9: Eno's Progressive Rock Music ('Pop songs')". Brian Eno: His Music and the Vertical Colour of Sound. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN0-306-80649-5. Archived from the original on v December 2006.

- Tamm, Eric (2003) [1990]. "Chapter Ten: Guitar Craft". Robert Fripp: From crimson king to crafty master. Faber and Faber. ISBN0-571-16289-4. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2012 – via Progressive Ears. Zipped Microsoft Discussion Document

- Timofeyev, Oleg 5. (1999). The golden age of the Russian guitar: Repertoire, functioning do, and social function of the Russian seven-string guitar music, 1800–1850 (PhD dissertation). Ann Arbor, MI (published 2006). pp. ane–584. OCLC 936747346.

- Vincent, Randy (2011). "Affiliate II: Tweaking drop 2". Jazz guitar voicings. Vol. I. Sher Music Company. ISBN978-1457101373.

- Whitesell, Lloyd (2008). The music of Joni Mitchell. Oxford University. ISBN978-0-19-530757-3.

- Willmott, Bret (1994). Mel Bay's consummate book of harmony, theory and voicing. Mel Bay Publications. ISBN156222994X.

Further reading [edit]

- Bay, William (2008). Deluxe guitar chord encyclopedia: Instance-size edition. Mel Bay Publications. ISBN978-0-7866-7522-7.

- Kirkeby, Ole (Baronial 2013). "Welcome to M3 Guitar Version three.0!". M3 Guitar. Archived from the original on 11 April 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- Patt, Ralph (1962). Guitar chord lexicon. H. Adler.

Berklee College of Music [edit]

Professors at the Section of Guitar at the Berklee College of Music wrote the following books, which like their colleagues' Chapman (2000) and Willmott (1994) are Berklee-course textbooks:

- Goodrick, Mick (1987). The advancing guitarist: Applying guitar concepts and techniques. Hal Leonard Corp. ISBN0881885894.

- Goodrick, Mick (2003). Mr. Goodchord'south almanac of guitar phonation-leading: Proper name that chord. Mr. Goodchord's annual of guitar vocalism-leading: For the year 2001 and beyond. Vol. 1. Liquid Harmony Books. ISBN0971185808.

- Goodrick, Mick; Miller, Tim (2012). Creative chordal harmony for guitar: Using generic modality compression. Berklee Press. ISBN978-0876391280.

- Peckham, Rick (2007). Berklee jazz guitar dictionary. Berklee College of Music. Ha Leonard. ISBN978-0876390795.

- Peckham, Rick (2009). Berklee stone guitar lexicon. Berklee College of Music. Hal Leonard. ISBN978-0876391068.

External links [edit]

- Interactive Guitar Chord Database

- Guitar at Curlie

- Chord Intervals

- Guitar Lessons at Curlie

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guitar_chord

0 Response to "Chords & Lyrics to John Cale / You Know More Than I Know"

Post a Comment